Hold device in landscape orientation

Best viewed full screen

"You are mad."

The border guard couldn't fathom why we, by choice rather than need, would enter the disputed territory of Kosovo.

"Much better to go to Bosnia" he said, a country which, to most minds in 2005, was mainly still associated with massacres and genocide. And yet nonetheless superior to our destination.

Certainly the example of a landmine warning sign wasn't auspicious.

Nor was the drama we viewed while waiting for an entry permit. A guard marched a young boy off a crowded coach, ordering him to empty his backpack onto the road. Once done, the guard delivered two powerful smacks to his backside, while the other passengers looked on with weary ambivalence.

Six years earlier, Kosovo, and its capital Pristina (seen here), were being consumed by the latest war to wrack the Balkans, as Yugoslavia tore itself apart across a decade of bloodshed.

Yugoslavia shrank through the 1990s as its components broke away to form new nations. Slovenia, Croatia, Macedonia, and Bosnia-Herzegovina all gained independence in this turbulent period.

Only two republics remained within Yugoslavia: Montenegro, and its much larger neighbour Serbia.

In Kosovo, an autonomous province of Serbia, a non-violent independence movement led to an armed insurgency by the Kosovo Liberation Army (KLA) against the Federal military and police of Yugoslavia.

Fighting grew increasingly bitter. Foreign nations were pulled in, culminating in a ten-week bombing campaign by NATO that compelled the Serb withdrawal from Kosovo.

An international peacekeeping force, KFOR, then entered, and have remained a visible presence.

Protected by KFOR, the United Nations assumed civil administration.

Although not part of the terms of the Serb withdrawal, Kosovo declared independence from Serbia in 2008. Considered illegal by Serbia and its ally Russia, as of 2017 only two-thirds of UN member nations have recognised Kosovo's independence.

Protected by KFOR, the United Nations assumed civil administration.

Although not part of the terms of the Serb withdrawal, Kosovo declared independence from Serbia in 2008. Considered illegal by Serbia and its ally Russia, as of 2017 only two-thirds of UN member nations have recognised Kosovo's independence.

Protected by KFOR, the United Nations assumed civil administration.

Although not part of the terms of the Serb withdrawal, Kosovo declared independence from Serbia in 2008. Considered illegal by Serbia and its ally Russia, as of 2017 only two-thirds of UN member nations have recognised Kosovo's independence.

By 2005, combat operations had ended. But tensions remained.

This graffiti, Albanian for 'self-determination', reflects the frustration of some Kosovars about the extent of foreign involvement in the determination of Kosovo's political future.

As throughout the Balkans, religion and ethnicity are the faultlines of Kosovo's conflict.

The vast majority of Kosovo's 1.5 - 2 million inhabitants follow Islam. They are also ethnically and linguistically Albanian, in contrast with its Christian, Slavic neighbour Serbia.

At a newly rebuilt petrol station, we were invited to join a lunch with its owner in the attached restaurant. Noting the damage and rebuilding we'd seen, I asked if it was personally awkward for Serbs and ethnic Albanians to interact. He replied, confidently and earnestly, that the past had been forgiven. "We are all brothers."

I was taken aback by his remarkably compassionate response. So the shock was all the greater when he continued: "You know who the real enemy is?", pausing and waving a finger at me. "It's the Jews."

I didn't perceive any tourist activity in Kosovo, and so in our old campervan we were a conspicuous novelty.

Here we are stopped by foreign policemen training local counterparts under a UN capacity-building program. They were excited to see us. One said I should have a photo wearing a UN cap. More precisely, his colleague's cap.

The northern areas of Kosovo border Serbia, and a sizeable population of Serbs still lived here. Tensions were high, and periodically flared into violent clashes.

Grenades had been used for attacks in the surrounding hills over the last few days. The police warned us to be careful.

So for the next photo I brought out my sword. Which surely put their minds at ease.

We drove to the flashpoint town of Mitrovica, heeding the UN's warning not to exit our vehicle.

Mitrovica was a microcosm of the broader ethnic conflict. The war displaced thousands from their homes: Serbs now lived north of the river, Albanians to the south.

Bridges across the river had become the focal point of ongoing ethnic clashes. Only the previous year, hundreds were injured and many killed in riots and gunfire.

The costs of war were still evident, despite years of rebuilding.

Most noticeable were the shells of destroyed buildings, and heavy cratering in some roads.

Signage wasn't always complete. KFOR created its own language-independent signs using animal silhouettes.

In darkness we became stuck in a town, all roads perplexingly returning to the same roundabout. Seeking directions, I tentatively entered an illuminated building, unmarked but with an open door. Inside, it was pristine, big, and devoid of either people or goods. Except for one wall with hundreds of bottles of a single brand of vinegar.

A man in a leather jacket appeared. Shortly thereafter, a second man came from outside. He handed over a wad of cash. I got free vinegar. With the language barrier too great for directions, the second man bid us follow his car. He led until we were out of town, pulled over, waved, and drove back.

While damage to infrastructure is readily apparent, the harm inflicted at a personal level by conflict is usually imperceptible to outsiders. The longing for absent friends and family. Homes and treasured possessions lost. Uncertainty. The lingering shadow of past trauma. All felt so sharply, yet to you invisible as on the street they pass by.

This fence is a rare exception, a tangible reminder of the personal cost. Even five years after the war, it still bears the faces of missing loved ones.

While damage to infrastructure is readily apparent, the harm inflicted at a personal level by conflict is usually imperceptible to outsiders. The longing for absent friends and family. Homes and treasured possessions lost. Uncertainty. The lingering shadow of past trauma. All felt so sharply, yet to you invisible as on the street they pass by.

This fence is a rare exception, a tangible reminder of the personal cost. Even five years after the war, it still bears the faces of missing loved ones.

While damage to infrastructure is readily apparent, the harm inflicted at a personal level by conflict is usually imperceptible to outsiders.

The longing for absent friends and family. Homes and treasured possessions lost. Uncertainty. The lingering shadow of past trauma. All felt so sharply, yet to you invisible as on the street they pass by.

This fence is a rare exception, a tangible reminder of the personal cost. Even five years after the war, it still bears the faces of missing loved ones.

Taken into the home of a local man working with NATO, we heard about the continuing struggles of daily life.

On the floor of the bathroom lay a pink plastic clamshell. It might otherwise have served as a toddler's sandpit. Here it was for flushing the toilet.

When tap water was available, it was filled. When there was none, it would be tipped into the toilet's cistern to manually flush it.

Feeling guilty about using up their precious water, mostly I would sneak outside to use our van's bucket instead.

Electricity was similarly intermittent, necessitating creativity and forbearance. Sitting near noisy generators wasn't dissuading these cafe goers. In the home, mealtimes now align with the local electricity schedule.

The son where we stayed didn't speak English, but found a way to interact once he learned we were Australian. With an arm full of cables, he rigged the TV and DVD player to a car battery, then played us Steve Irwin's The Crocodile Hunter.

Over beers poured from 2 litre plastic bottles, we discussed Kosovo's turbulent recent history with our host. He recalled how the withdrawing Federal army sent tanks into the suburbs and systematically destroyed house after house, sparing only those belonging to Serbs.

Yet it cost many Serbs their homes too, for to have one amidst your newly-homeless neighbours is no easy thing, and soon many had departed.

The Albanian flag was flown prominently in Kosovo, which had no official flag until 2008.

So too was the USA's flag. The majority of Kosovars were expressly grateful to NATO, and particularly America, for the bombing campaign that drove Federal forces back to Serbia and Montenegro.

Many shop counters had a little display holding both flags. Both were carried by this raucous wedding procession.

At a time when Western media was laden with criticism of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, it was a surprising counterpoint to see such appreciation of Western military interventionism.

On a main road in Pristina, this billboard offers sympathy following terrorist bombings a fortnight earlier in London.

Understandably less grateful for NATO's involvement were Serbia and Montenegro.

NATO relied on its overwhelming airpower, rather than deploy ground forces. One thousand aircraft were assembled, and more than 30,000 missions flown. The B-2 stealth bomber saw its first use, flying 30-hour missions direct from the USA. The ten week campaign targeted both military units and infrastructure, such as bridges.

Understandably less grateful for NATO's involvement were Serbia and Montenegro.

Rather than deploy ground forces, NATO relied on its overwhelming airpower. One thousand aircraft were assembled, and more than 30,000 missions flown. The B-2 stealth bomber saw its first use, flying 30-hour missions direct from the USA.

The ten week campaign targeted both military units and infrastructure, such as bridges.

Targets hit in the Federal capital Belgrade included the Chinese embassy (called an accident by the US) and this Ministry of Defence. Bombed multiple times, it remained unrepaired five years later.

The intention is to preserve it in its damaged state as a memorial to the victims of NATO's attacks.

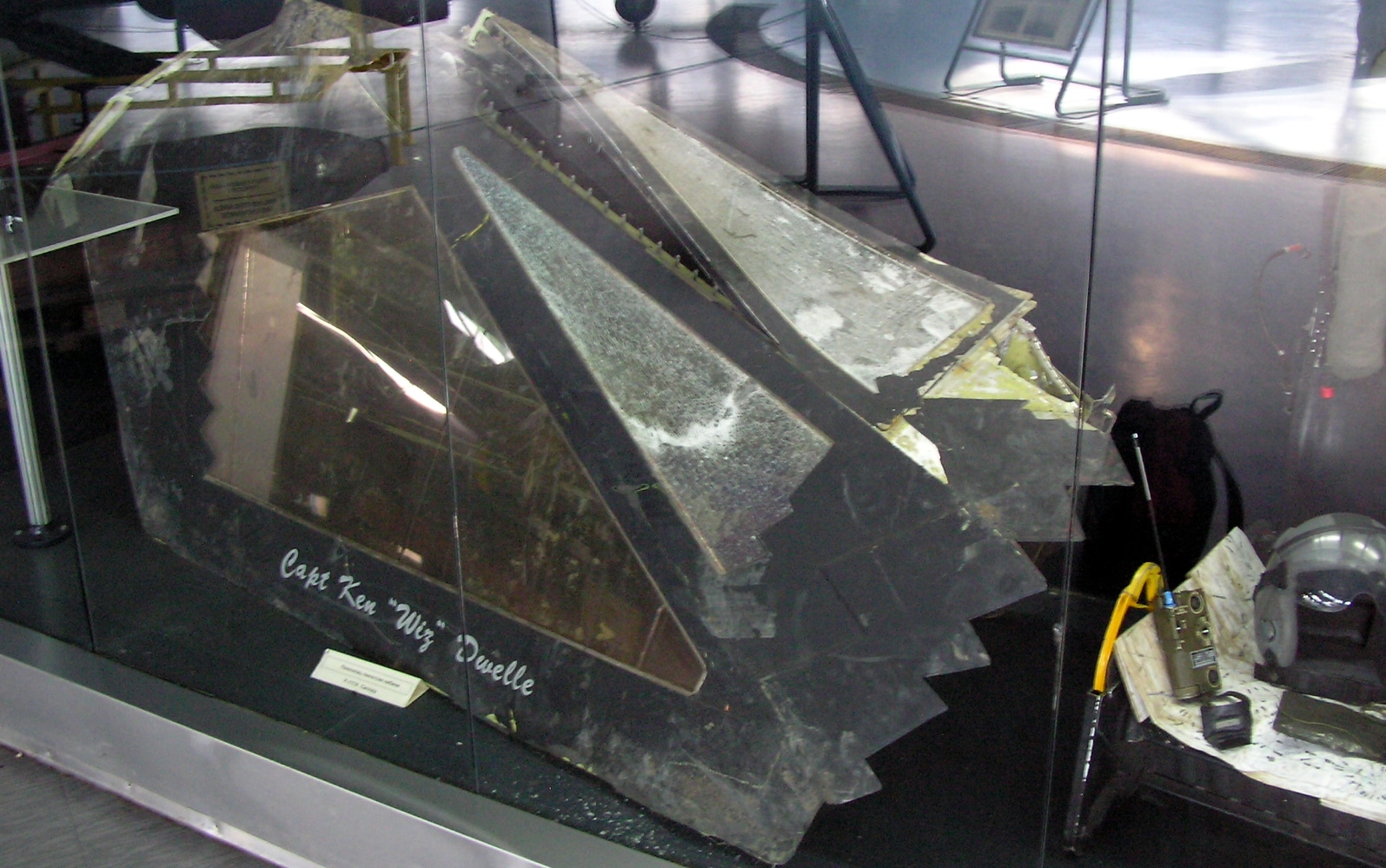

Museums in Serbia proudly present captured NATO items.

Displays emphasise the disparity in power between NATO and Federal forces. American use of (potentially toxic) depleted uranium shells is highlighted.

Visitors to the Aviation Museum can buy a small piece of destroyed NATO equipment as a souvenir. Chosen out of three options, the debris comes with a photo of the aircraft in its 'before' condition.

I opted for a piece of the only F-117A ever shot down. Once home, a locksmith had the unique experience of drilling holes into part of a stealth fighter. Then I wore it as a bracelet.

------------

Tensions were very much alive in Kosovo and Serbia in 2005, and they remain present today. Yet this wreckage, this reminder of war's destruction, is also a sign of healing. The pilot named on the cockpit has since visited the museum, and become friends with the Serb soldier who shot him down.

Did you like this article?

Do you like this site?

Brilliant blog. Great story telling. Thanks!