It all begun with Mrs Troffea. In the summer of 1518 she went onto a street in Strasbourg, a large town in what is now France. And there she began doing something familiar yet, in context, strange. She began dancing.

Strasbourg has more than its fair share of claims to fame. It was where Gutenberg created Europe’s first proper printing press. Its cathedral was the tallest structure in the world for over two centuries, a record held for longer than by any building since. Today it is one of the capitals of the European Union.

But that is not all. Strasbourg was also the site of perhaps the best-documented case of a dance epidemic. And Mrs Troffea was Patient Zero.

The Dancing Plague of 1518

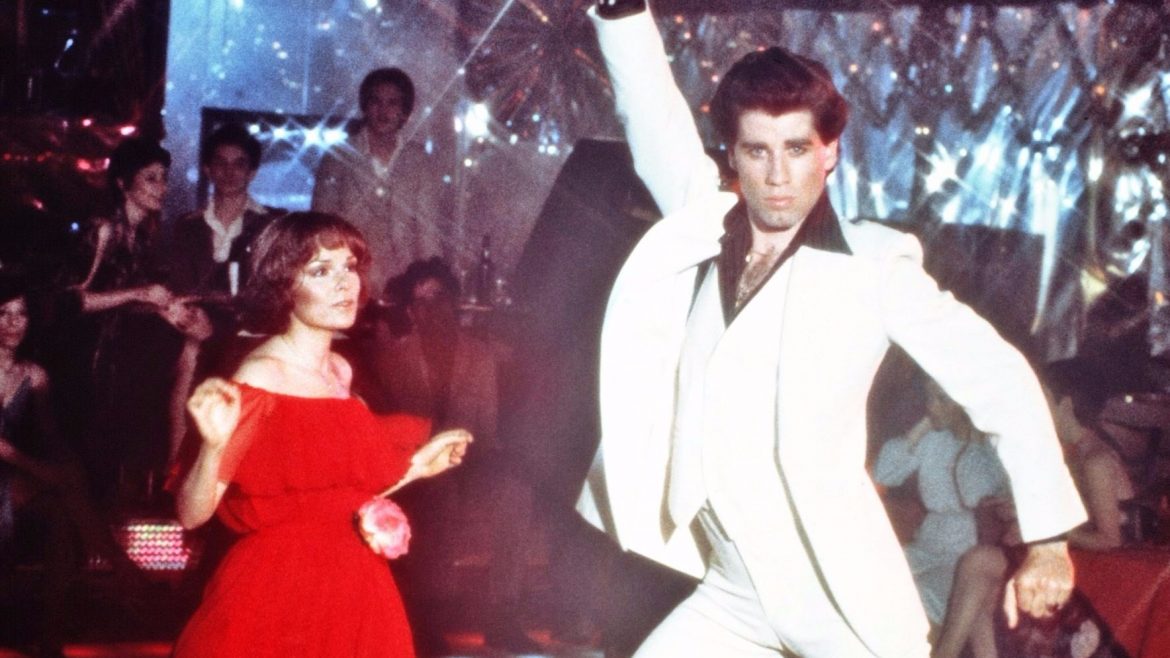

If someone made a game for the PlayStation or Wii called ‘Dance Epidemic’ then I would almost certainly buy it. Similarly, the citizens of Strasbourg weren’t against buying into what Mrs Troffea was offering.

For you see, Mrs Troffea didn’t just dance for a while and go home. Oh no. She danced non-stop for at least four days. A week later, there were 34 people dancing together. After a few more weeks the number had swelled to around 400. Many danced until they collapsed and died.

Authorities were alarmed. Astrological or supernatural causes were ruled out – this was the 1500s after all, not the primitive 1200s.

It was thought that recovery hinged on the sufferers becoming ‘danced out’. To this end, places were opened for dancing, a stage built, and musicians hired. But alas, this had the opposite effect, and the number of dancers continued to grow.

What was going on?

The Tarantula

It would be easy to write this off as some weird ye-olde story, if it was a once-off. But it wasn’t. We know of something similar happening in southern Italy around the same time, called ‘tarantism’.

Tarantism is named after the tarantula. Being bitten by this spider was thought to be the means that the infliction spread. Men and women would publicly dance themselves into a frenzy, ostensibly as a cure to the spider bite.

Others report that the affected would lack vigour and appear discoloured, until being gradually and, ultimately, extremely revitalised by the playing of a guitar. Tarantism acquired its own specific form of music, the tarantella, evolutions of which survive to this day.

However, bites from this spider are not medically significant. Possibly another, more dangerous local spider was the mistaken source. But more likely it was a form of dancing mania.

Dance Mania

Similar events were recorded elsewhere in Europe, across a span of centuries until largely ending in the 1600s. Typically it was contagious, but sometimes the affliction remained within a small group. Instances are recorded involving numbers from only one man, to tens of thousands of people.

They sound implausible, and the level of exertion reported is often beyond what modern athletes could endure. Yet contagious outbreaks of dancing are attested to by a variety of reputable sources. Specific instances are frequently corroborated by multiple independent, contemporary authorities like church sermons, notes from local doctors and historians, and the proceedings of city councils. This isn’t some fringe theory, rather they are a phenomenon accepted by the modern historical consensus.

In general, the dancers were vigorous yet orderly. This wasn’t always the case however. Participants could be naked, make obscene gestures, mimic the movement of animals, or have public sex. Some dancers assaulted onlookers who didn’t join in.

Mostly, the afflicted danced until they collapsed from exhaustion, often days after they began. The unlucky died dancing, frequently from heart attacks. Broken ribs were known, and ailments such as chest pains, convulsions, and hallucinations manifested while dancing. An outbreak in 1374 saw thousands of people across several towns dancing in agony, screaming of terrible visions, begging for their souls to be saved.

What was causing the dance manias?

The authorities at the time attempted various cures, including isolation, prayer, and exorcism. St Vitus had a prominent role, with many dances ending at sites devoted to this saint. Musicians were sometimes hired to play to a group, including to lead them away to places where they would do less harm. However, sometimes the music led to more people joining in.

Today, like then, we have no clear explanation of the phenomenon of dance mania. Mooted causes include:

- repressed religious cults using dance mania as a cover for performing banned rituals;

- people jumping onto the bandwagon for the chance to break taboos;

- some participants being involved due to mental illness or peer pressure; and

- ergot poisoning. Ergot is a fungus that can grow on various grains. It produces a chemical related to LSD, which when consumed can cause strange effects such as hallucinations, paralysis, muteness, fever, mania, and tremors.

Perhaps the strongest medical explanation is that the dance manias were an outbreak of mass hysteria.

What is mass hysteria?

In general terms, mass hysteria is the spread of illusionary fears amongst a group. A classic example is the alleged alarm caused by the 1938 radio broadcast of ‘War of the Worlds’, which was supposed to have led to panicked Americans fearing on an ongoing Martian invasion. In some cases of mass hysteria, though not all, the participants exhibit unwanted and unattributable physical effects. Indeed, the shared ailment is frequently the focal point of the hysteria.

Though a compelling physical cause won’t be identified, nonetheless the affected person exhibits very real physical symptoms. Typically these symptoms are related to anxiety, and can include physically obvious symptoms such as fainting, rashes, or vomiting. Women tend to be affected more than men, as do younger people, and those in a discrete environment such as a school or factory.

Effects may be short-term, lasting less than a day. But they may also appear gradually and last for weeks or months, particularly the more extreme cases involving motor symptoms like shaking and trances. Though by definition unexplained by anything tangible, it is likely that some of the recorded outbreaks of mass hysteria had a physical cause, just one that couldn’t be identified at the time.

Mass hysteria is more likely if a group is undergoing a shared stress, especially where the group members have little power. In the case of the dance mania, the outbreaks often aligned with especially difficult circumstances, such as food shortages, the spread of disease, and weather catastrophes. John Waller, a writer on medical history, observes that the affected regions possessed an enduring belief that divine beings could inflict uncontrollable dancing as a punishment. Psychological distress due to harsh living facilitated some individuals falling into a trance-like state, in which dancing was prominent due to the local cultural focus. Seeing people affected in this way strengthened existing beliefs and assisted the dancing mania to spread within the distressed community.

Dancing plagues are crazy – is all mass hysteria amusing?

I’m glad you asked. Certainly not to the afflicted, or to those around them. Fortunately, we are neither.

Putting to one side the associated upheaval and suffering, one of the more ludicrous examples of mass hysteria was the Tanganyika Laughing Epidemic of 1962. Sounding like something invented by Monty Python, the Laughing Epidemic began with three girls laughing at their boarding school. It ended around a year later after having spread to 1000 people and shut fourteen schools.

Mostly affecting schoolchildren, especially girls, no responsible disease or toxin could be identified. Symptoms would last for a few minutes to a few hours, abate, and then usually reoccur, in one case across 16 days. In addition to the uncontrollable laughter, the affected would cry, violently resisting restraint, and seemed to be frightened of something or someone but would not explain what or who. More comically, symptoms included random screaming and flatulence.

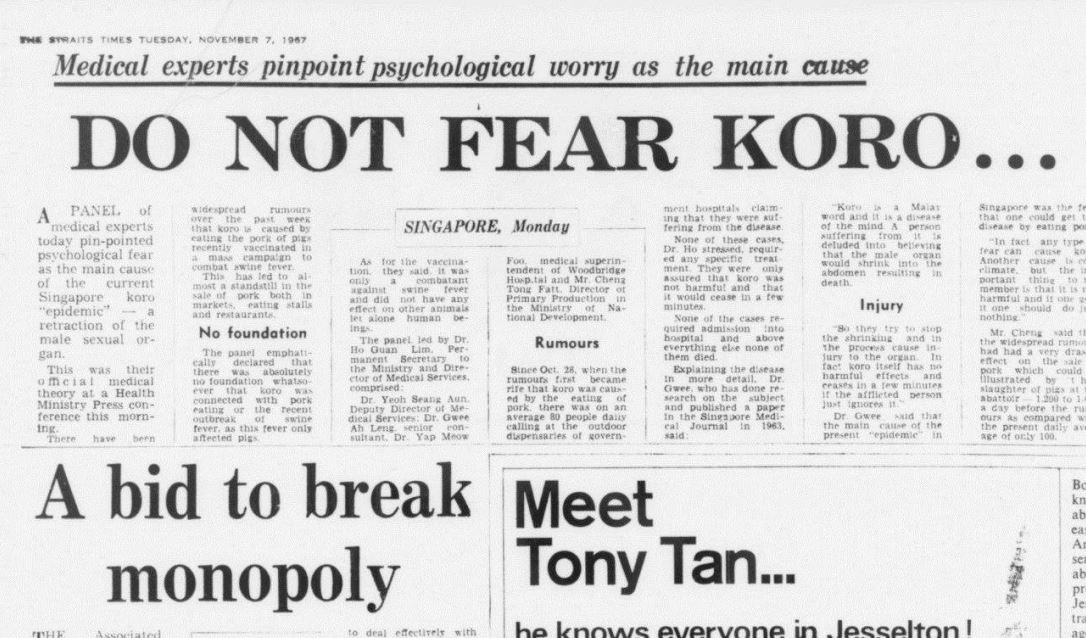

Finally, there are the mass hysteria known as colloquially as ‘penis panics’. This phenomenon deserves its own article but suffice to say those affected are overcome with the irrational fear that their genitals retracting into the body (including, for women, nipples retracting into breasts). These fears are so strong that people have resorted to mechanical techniques to prevent the supposed retraction. This includes attaching weights to the penis or putting nails through nipples.

A penis panic can affect hundreds or thousands of people as it spreads through communities. They have been recorded throughout the world, with Africa and India hotspots in recent decades. Aspects of the panics vary between outbreaks. For example, penis panics in China typically include a feeling of impending death, whilst those in Africa focus more on genitals shrinking rather than retracting inside the body. As a cure, traditional Chinese medicine might prescribe hitting gongs, consuming the penis of assorted animals, or beating the patient.

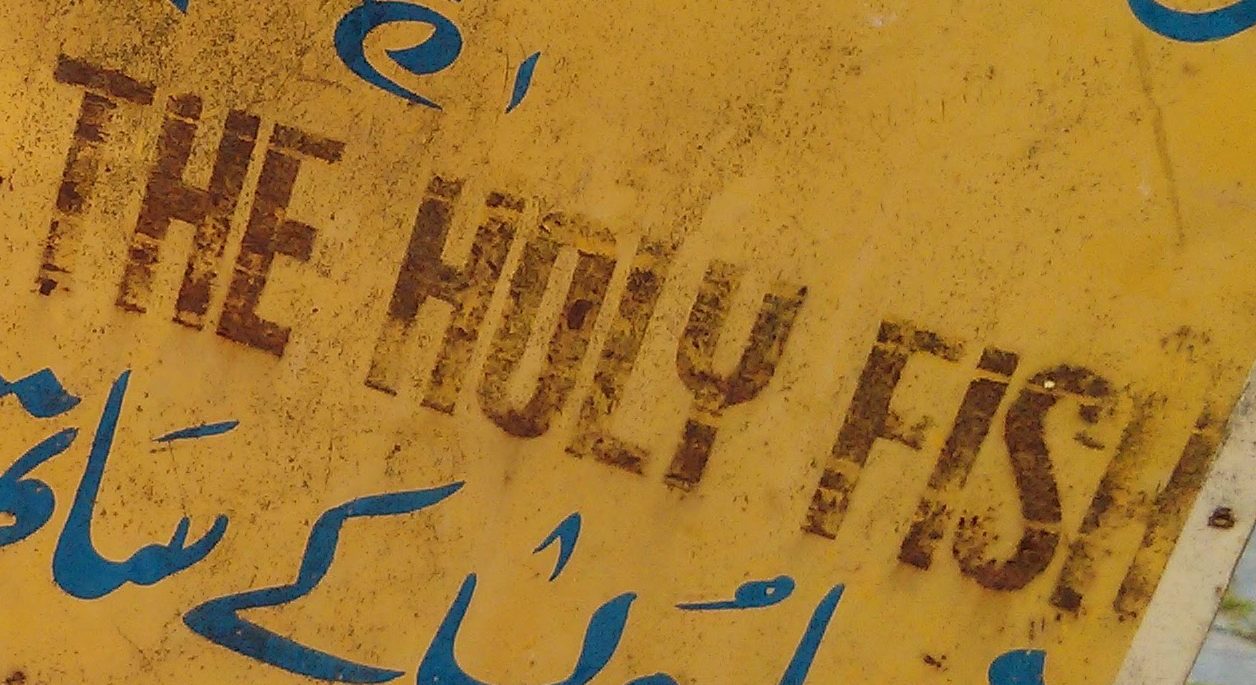

The purported cause of the genital disappearance also differs. In 2001, mobs in Benin publicly attacked people who they suspected had stolen penises by using an incantation or handshake. The mobs burned at least four people to death. At various times, blame has fallen on Vietnamese food, witchcraft, meat from vaccinated pigs, and malevolent fox spirits.

This brings to a close our look over mass hysteria, and particularly the phenomenon of dance manias. Next time you want to dance all night, don’t party like its 1999. Party like its 1518, Strasbourg-style.

Did you like this article?

Do you like this site?