“Cheer up, there’s plenty more fish in the sea”.

Any breakup survivor will recognise this sentiment. It isn’t just an empty platitude either. Rather, it’s a timely reminder that no matter how special your former partner was, however unique your connection seemed, they are in fact pretty much replaceable.

“What? Replaceable? No, no way” I hear the romantics cry, recoiling from such heartless, near-sacrilegious words.

Yet where did they find their true love, that one person alone in all humanity who they were destined for? I’ll wager it wasn’t amongst the teeming millions of some far-flung megacity, but improbably (and conveniently) much closer to home, sharing the same tiny corner of our vast world.

Perhaps those who find their soulmate are all beneficiaries of statistically implausible strokes of good fortune? After all, ask any patriot to choose the greatest country, or a worshipper to name the one true faith, and their answer will likely match whichever nation or religion they just happened to be born and raised in. What luck!

If one soulmate can be found then surely there’ll be thousands, likely millions, of others who could also do the job. Not romantic sure, but inescapably logical. The sea is vast, and it teems with fish.

And yet to a single person it can feel like the sea is emptying. Each year more people in your age group couple up. As a rough test (and because I could do it whilst watching Netflix) I counted through my Facebook friends and of those whose relationship status I knew, 84% are partnered. True, not all relationships last. But they do tend to become more permanent as we move through life. That’s a lot of people who’ve taken extended holidays from singledom.

So, what happens to the dating pool as we age? When and how fast does it dry up? And how many fish are still left?

To answer these questions I’ve analysed two recent population surveys. Because all comforting words to friends (or efficient dating strategies) should be built on a solid foundation of data analysis.

Finding the Data (skip this section if you just want the answers)

The specific scenario I set out to answer is this: imagine you’re in a bar, or on a bus, or at the shops. You meet someone, feel a rapport, and consider asking them out (I assume this is how dating works). But what are the chances that they’re already in a relationship? So keep in mind that I won’t be talking about the raw number of single people at a given age, but rather how likely it is that any random person of that age is single.

The first port of call to explore this topic is the 2016 Australian Census, a 5-yearly compulsory survey of the entire population. Note to international readers: this research uses Australian data but I anticipate it will largely hold true across many, especially Western, countries that share relatively similar age structure, religious adherence, economic development, and broad social mores.

The Census has two questions on relationship status, and neither are perfect for this purpose. The first doesn’t count de facto / domestic partner relationships (thus essentially excluding anyone living together as an unmarried couple). The second question, and the metric I’ve chosen,ref only covers 90% of the population but does give the number of people in de facto relationships, as well as registered marriages or neither.

This gives us most of the required data but it misses one important category. Anyone who has a partner, but isn’t living with them, is lumped into the ‘not married’ category.

As you might expect, the share of relationships that don’t involve living together varies greatly with age. In our early-20s, almost 60% of partners live separately, but ten years later only 14% do.

So if we do our best to bring all the data together, what do we learn?

The Answers

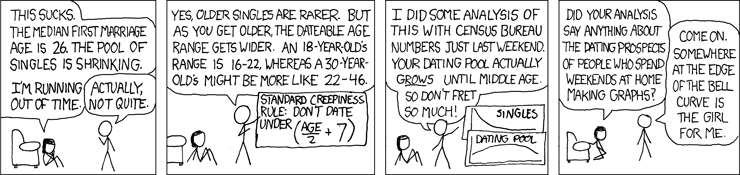

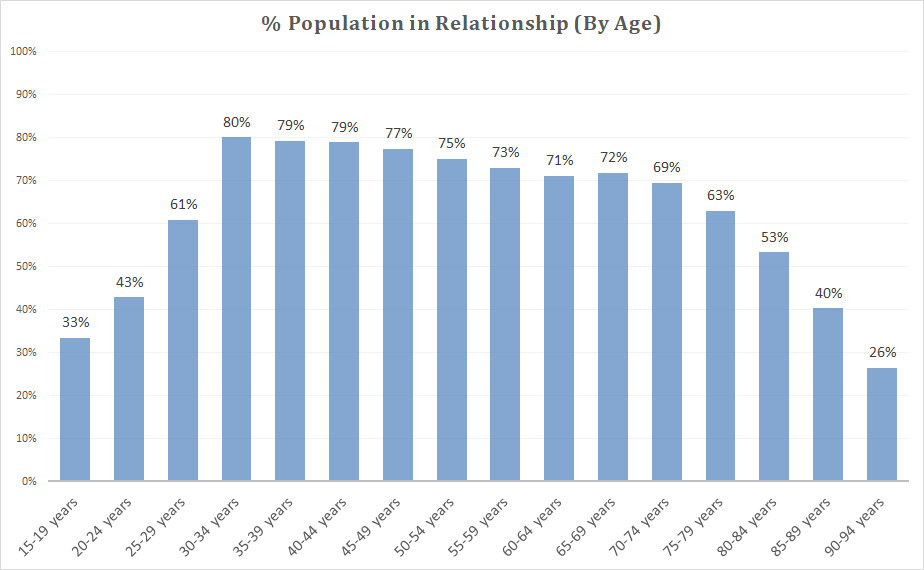

- The percentage of the population that is coupled (i.e. is in any of the reported forms of relationship) rises in each age group up until the early-30s. Then the proportion of couples declines very gradually until the late-70s. So that is good news if you’re not coupled by your mid-30s but wish to be. Sure, your fertility is declining but at least the proportion of available partners isn’t – the dating pool has reached ‘peak dryness’. From this point onward the tide is rising, albeit very slowly.

The chart above shows the trend. In their late teens, 33% of people are in a relationship. The peak, in the early-30s, is 80%. So for most of adult life, from early-30s until old age, there is a roughly 1-in-4 to 1-in-5 chance that any random person is single.

As a bonus, here are two other titbits that came from the analysis:

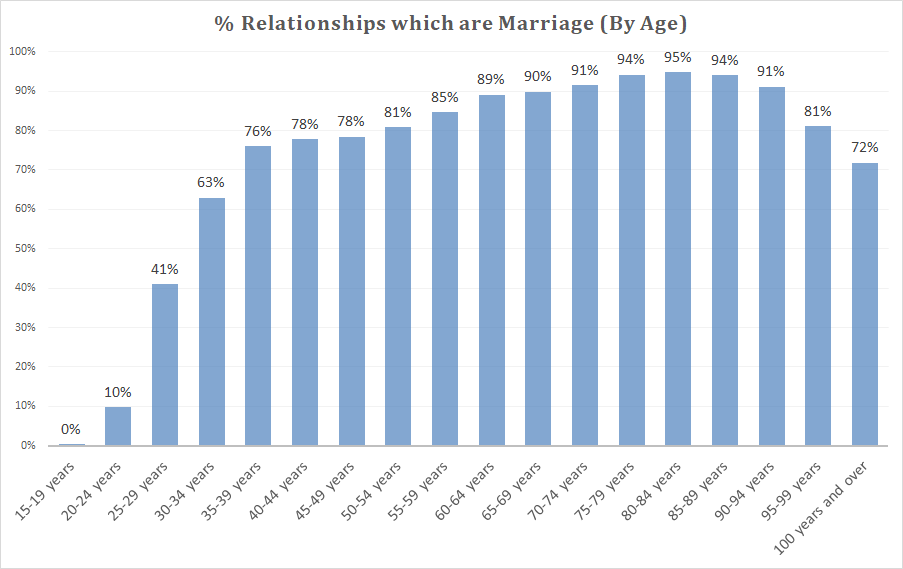

- There is one way that dating life gets consistently easier. To the extent that wedding rings are worn, spotting those who are off the market becomes increasingly obvious. For people aged in their 20s, only a quarter of relationships on average involve marriage. By the late-30s, this ratio has flipped – now it’s those who aren’t married that account for only a quarter of relationships. This trend continues steadily across the decades until non-marriages make up only a tiny portion of all relationships.

Keep in mind that throughout this article, all figures relate to the age group you’re hypothetically interested in, not to your own age. If you’re 22 and looking for a sugar daddy/mumma in their 40s, consult the data for the 40-44 and 45-49 age groups, not the 20-24 group.

- While at least 20% of people at any age are single, by the end of a typical lifespan only 4% of people will never have been married at some point.

Particularly when interpreting this chart, we should keep in mind that coupling practices change over time, and the statistics we are looking at only partially account for this. For example, the numbers in the 80-84 category reflects the coupling habits of people born in the 1930s, and aren’t necessarily what we’ll see when younger generations reach their 80s.

Does availability vary between genders?

Yes, particularly towards the ends of the age range.

- Women still reach ‘peak unavailability’ in their early 30s. From then on they become steadily more available, though the rate of change is quite small until reaching their 70s.

- In comparison, the unavailability of men doesn’t reach its highest point until their late-40s. That said, the peak is only slight: male availability is essentially the same from their early-30s until their 80s.

Women in their early-30s are the least available of any combination of age and gender. At this point only 15% of women are not coupled, compared to 25% for men at the same age. At any age, male availability never drops below 20%.

What we see is a roughly similar pattern in availability between the genders, but with more extreme changes for women. In comparative terms, women become less available than men, and sooner, and then become more available, sooner and more rapidly.

And different locations?

Yes, though not as much as you might think.

Working from 2011 Census data, and applying the HILDA survey’s 9% figure for non-residential relationships, I took Canberra as an example. Home to almost half a million people, Canberra has an unusual layout (it is a recent, planned city) but its broad urban morphology is nonetheless typical of an Australian city: cores with higher-density residential, quickly transitioning to extensive (and often quite new) suburbia, and with considerable variation in suburb size.

At one extreme, the proportion of single people within a suburb falls as low as 18%. As you might expect, suburbs in which residents are overwhelmingly in relationships (such as Bonner, Harrison and Forde) tend to be recent suburban developments on the periphery of the city – affordable areas popular with young families.

At the other end, no suburb has more single people than coupled. It does come close though, with half a dozen suburbs comprised of 40%-49% singles. And these suburbs are surprisingly varied in nature. Yes there are the inner-city suburbs such as Braddon, Reid and Turner – suburbs popular with young professionals and university students, with a mix of new apartments and larger, ageing housing stock. But they are topped by Symonston and Oaks Estate, two small suburbs that many Canberrans would struggle to place on a map. The former is a mostly undeveloped area where residents live primarily in long-stay caravan parks, while the latter is removed from the rest of the city and contains an exceptional amount of social welfare housing.

So in Canberra at least it seems relationship-seekers are well catered for with demographic choice.

More broadly, we can anticipate that locations with a predominately young or elderly population will tend to have higher levels of availability, though this may not be visible in the data due to the exclusion of people living in non-private dwellings (like colleges or nursing homes). If we add additional categories, such as gender, we can expect that the range between locations with the highest and the lowest availability will grow larger. Consider for example the consequence of gender imbalance in remote townships dedicated to male-dominated activities such as the military or primary industries like mining, fishing, agriculture, or forestry. However, the impact of remoteness is likely to be diminishing relative to earlier generations, as technological and economic changes promote fly-in fly-out employment that facilitates remote workers maintaining relationships with partners who live elsewhere.

In Summary

The proportion of single people, particularly women, drops rapidly until they are in their early-30s. At this point only 1-in-7 women are single, and 1-in-4 men. Men remain about this available for the rest of an average life, while women become more available every year, overtaking men around the mid-40s.

These figures ought to be treated as maximums: some portion of those who are single will (irrespective of your attractiveness) be permanently uninterested or incapable of coupling, or at least temporarily so, perhaps such as after a recent breakup. And of course they say nothing about the ratio of single to partnered people in your particular workplace, gym, or dog park (or wherever it is that romances are kindled).

And finally, a few parting observations:

- Accept a wider span of ages and your dating pool grows much larger (and vice versa). The average likelihood that someone is single may go up or down (it will roughly be the average of each age group), but the raw number of available singles will increase.

- The same applies to genders e.g. if you’re not straight, your dating pool is more of a dating puddle. That said, a puddle might be all you need. And a big city’s puddle will be larger than a small town’s pool. Plus some restricted dating pools come with the silver lining that your potential dates have fewer choices available that aren’t you.

- Especially in the later years, the raw number of potential partners will tend to decrease…because they’ve died. This doesn’t necessarily hurt availability though. If it’s true what TV has told me about the gender balance in retirement hotspots like Florida, old age is a good time to be a single man.

- Individual results will vary. If you ask out 100 people and no-one says yes, well there may be factors in play beyond statistics.

Did you like this article?

Do you like this site?