I hate waste. I also hate being sick and doing unnecessary stuff.

Unfortunately, when it comes to food, avoiding these problems often involves contradiction. Sure, throwing out this food would be the safest. But then, you know, I won’t have it. And I want to have it, because food is great and I probably paid for it and/or prepared it too. Is discarding it really necessary? How do I make an informed decision that weighs the risks and benefits of binning or using?

It’s hard to find balanced information, mainly because most communication in this space comes from entities like governmental health organisations. Their advice is understandably risk averse. Their messages must be conveyed quickly and unambiguously, and to people of all kinds, most of whom have a passing interest at best. Public health communication isn’t the place for listing caveats or exploring probabilities and degrees of certainty.

Secondly, their advice is intended to really address only one aspect of our decision-making. An important part undoubtably, as anyone who has had food poisoning can attest. But few agencies or health professionals will encourage you to eat the dubious takeaway in the fridge. After all, it’s their job to stop us getting sick. It’s not their job to help us avoid inconvenience or food waste or needless spending.

This article seeks to give a fuller picture of food safety and storage in the home. By understanding the basic principles we can make better decisions than if we follow only the standard advice. If you’d like to run a better kitchen, read on.

Why does food go off?

Two distinct factors cause food to spoil: microbes, and chemical reactions.

Food, like everything, is host to a plethora of micro-organisms: bacteria, viruses, yeasts, moulds, and parasites. Of these, it’s mainly bacteria and mould that damage the taste and appearance of food. Bacteria that makes food spoil are frequently harmless to health. Conversely, those that cause food poisoning don’t change the smell or taste of food.ref

Chemical reactions

An example of a chemical reaction in your stored food is when apple slices or cut avocado turn brown. This particular chemical reaction (called enzymatic browning) is related to caramelisation and the browning of bread. It’s not a safety issue, and in fact it’s used to enhance the quality of some foods, such as coffee and raisins.

How can food make us sick?

Unsafe food inflicts gastroenteritis on seven Australians, on average, every minute. That’s over 4 million per year, with similar rates in the US and Canada.ref Of these, around 100 cases daily are so bad that the victim requires hospitalisation.

The cause of this illness could be food you just finished eating, or something from days or even weeks ago. ref

Each type of microbe can be harmful, but the main culprit is bacteria. Most forms are harmless. Many are beneficial. The remainder can cause anything from mild discomfort, to death. The young, elderly, sick, and pregnant are particularly vulnerable.

Our body is not a welcoming neighbourhood for migrating bacteria. Yet ingest too many and enough will survive to start an infection. For some species, this might be a few dozen (and for viruses, potentially just a single particle). For other bacteria, we become infected only after consuming millions.

Bacteria can hurt us in two ways: they can break apart our cells and they can poison us with toxins. They can escape the stomach before our body even attempts to repel the invaders (via vomiting and/or diarrhea). The toxins can be created within our bodies during an infection, or may already be present in what we eat. Some toxins are more dangerous than the bacteria themselves. The bacterium which causes botulism makes a toxin so deadly that a single milligram could kill a million guinea pigs. Though I presume this hasn’t been proven in practice.

The #1 Antidote: Temperature

Conveniently, both spoiling and sickness are combatted primarily with the same weapon: temperature control.

Understand how temperature affects microbes and chemical reactions and you’re on your way to effective food management.

- Freezing greatly slows chemical reactions, and halts microbial activity (though doesn’t kill them).

- Refrigeration slows chemical reactions, and halts or slows microbes. ref ref

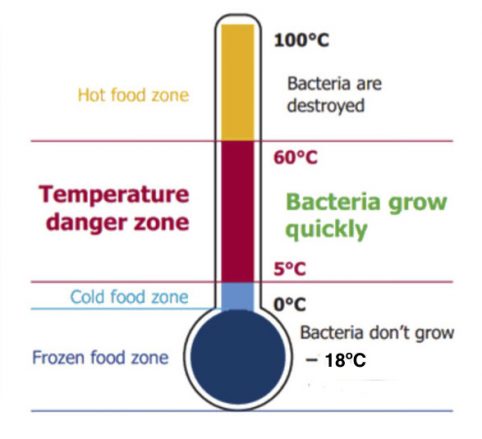

- Microbes are active i.e. replicating and producing toxins, between fridge temp and 60℃ (140℉), peaking around 40℃ (105℉). ref

- Above 75℃ (165℉), bacteria die, though any toxins will generally remain. ref

- Avoid food with an existing load of toxins, as once poisoned the food cannot be unpoisoned.

- Cook food to kill any harmful microbes.

- Prevent recontamination.

- Freeze to keep the food clean, or refrigerate to limit both toxins and damaging chemical reactions.

Over the following sections we follow a typical progression of food use: purchase, storage, cooking, freezing/refrigeration, and reheating.

At The Shops

All else is pointless if you’ve brought home bad food.

Avoid containers that are significantly damaged, or appear swollen.ref This is why the metal lids on glass jars have a centre that can pop out – if it has popped then the vacuum seal has been breached and the contents can no longer be considered sterile.

Date labelling varies between countries. Australia and New Zealand share a scheme that differentiates between a product’s use-by date and its best-before date. The table below compares their key elements.

Comparison of Food Labelling Dates

ref ref| Use By | Best Before |

|---|---|

| Safety Issue | Quality Issue |

| Health risk if consumed after date | After this date the quality may deteriorate, and no longer must meet any advertised claims. But still safe to eat. |

| Cannot be sold after this date. | Can be sold after this date. |

| Not required for food with a shelf life of more than two years. |

Both types of date only apply until the package is first opened. They also assume any directions are followed, such as keeping refrigerated where applicable. ref

How a food is packaged is important. While it may appear solid, moisture and gases do slowly pass through plastic packaging, at a rate determined by its type and thickness.ref Packaging can also interact with the food it contains.

In The Pantry

Faeces and soil are two of the biggest sources of food pathogens. This is why fruit and vegetables, particularly those eaten raw or unpeeled, should be properly washed. Disgusting things happen outdoors.

Shelf life can vary greatly between subtypes of a fruit or vegetable. For example, some varieties of avocadoes and apples can last around three times longer than others.ref

How to best store any given type of fruit and vegetables is surprisingly complicated, so that’ll be a later separate article. But two basic principles are:

- Unripe fruit and veg should generally be kept at room temperature. While some fruits and veg don’t ripen after harvest (e.g. grapes, citrus, berries) and can be refrigerated to delay spoiling, others are best kept out of the fridge until they reach the desired ripeness (e.g. tomatoes, bananas, stonefruit).

- Some fruits emit a gas called ethylene, particularly when ripe, which speeds up the ripening of nearby fruit. You can use this to your advantage, for example by separating fruit to slow ripening, or by placing one or more in a container to speed it up. Ethylene-sensitive fruit include bananas, avocados, tomatoes, apples, pears, mango, kiwifruit, and most stonefruit.

Prior to the widespread availability of refrigeration, food was smoked to improve shelf life. But now, food is often smoked just for the flavour – it is not necessarily any safer.ref

Even tinned products slowly degrade due to chemical changes, especially high acid food like fruit juice and tomatoes, or if the tins have been stored in a warm area.ref Once opened, exposure to air can cause tin or iron from the can to dissolve into the product. While this can affect the taste, many cans are now lacquered to prevent this leaching, and in any case is not a safety concern.ref

Cooking & Eating

Heat will kill essentially all harmful microbes: 60℃ (140℉) for fruit and vegetables, 65℃ (150℉) for seafood, 75℃ (165℉) for other meats.ref ref

Every part of the food needs to reach this temperature. To be certain, stick a meat thermometer into the centre. A less reliable method is piercing the thickest section and checking that the juices run clear (for chicken and processed meat). Failing that, visually it should be steaming hot, and feel very hot in the mouth.ref ref

An exception to the above are whole pieces of red meat like steaks and chops. For these, it’s only the surface that must reach 75℃ (165℉). This is because the interior has not been exposed to contamination through processing, unlike with sausages, burgers, rolled roasts, and tenderised and marinated meat etc.ref Note this exception doesn’t apply to whole pieces of poultry, as pathogens are significantly more likely to have penetrated below their surface.ref

Browning is not a reliable guide. Browned meat may be uncooked inside. Conversely, pink mince or poultry may be safe to eat.ref

Avoid cross-contamination. If something must be cooked before eating, then anything that touched it while raw should be cleaned before touching food that is ready to eat. For example, don’t put cooked meat back onto the original plate, or prepare salad on a chopping board used with meat. Similarly, don’t let risky items spread contamination in the fridge by dripping onto food that won’t be cooked before consumption. Illness-causing bacteria grow more quickly in food that they recontaminate post-cooking, as the heating has killed off competing bacteria.ref

The 3/5/10 Second Rule

Presumably we all recognise that this rule is less about science and more about eating off questionable surfaces without being socially ostracised. Nonetheless, it’s been the subject of numerous studies.ref ref Not all results are in agreement, but in general:

- While more time on the surface equals more bacteria, most of the contamination occurs instantly.

- Wet foods pick up more bacteria.

- The type of surface is important. Surprisingly, carpet transfers less bacteria than smooth floors.

- Even clean floors have potentially harmful bacteria. But many surfaces have more. Benchtops. Tables. Fridge and tap handles. Keyboards and phones. Items used to clean plates and cutlery, like sponges. Money. Light switches. Hands.

Thus in most environments, the worst place to retrieve food from is unlikely to be the floor.

Into The Fridge

Go a few days without a fridge and you’ll appreciate just what incredible inventions they are. To get the most from them, keep it set to 5℉ or less, and not so full that air can’t circulate.

Food safety experts advise that food can be kept safely between 5℃ (40℉) and 60℃ (140℉) for at least 4 hours, or between 21℃ (70℉) and 60℃ (140℉) for at least 2 hours.ref This is the general standard to which commercial food providers must adhere in many countries. The timeframes apply to any food that contains:ref

- Meat, including poultry and seafood

- Dairy

- Cooked rice and pasta

- Processed fruit, vegetables, nuts, eggs, or soy, for example salads and fruit packs

- Sprouts, and

- Dips.

It can take many hours for a big batch of food to cool all the way through, so it’s technically best to use smaller, shallow containers for any food that may be contaminated/recontaminated.ref

Interestingly, meat will last longer in the fridge when unwrapped. Wrapping keeps the surface of meat moist, which encourages the growth of bacteria. Allowing air to circulate around meat dries it out, which reduces the growth of surface bacteria. However, this may affect flavour and texture.ref

In contrast, keep refrigerated root and leaf vegetables in bags to retain moisture.

In lieu of guidance on the packaging, the table below shows how long an item should last for, at a minimum, once opened.ref ref

Minimum length of safe refrigerated storage

| Food type | Estimated minimum safe storage time |

|---|---|

| Fruit juice | 1-2 weeks |

| Cut fruit and veg | 2-3 days |

| Cream cheese, ricotta etc. | 10 days |

| Soft cheese | 2-3 weeks |

| Hard cheese | couple months |

| Seafood, chicken, minced meat | 3 days |

| Other meat | 3-5 days |

Reduced salt variants may store less long.ref

The Freezer

Frozen food stays safe indefinitely, as all microbial activity is stopped.ref

Any changes that do occur over time affect only appearance and taste. These are due to chemical reactions, such as fat oxidation in meat, that are slowed massively but not completely halted.ref The storage times shown inside some freezers are the manufacturer’s assessment of likely changes in food quality – consider them equivalent to the ‘Best Before’ dates discussed earlier.ref

Frozen meat naturally undergoes some colour change over time. Greyish patches (freezer burn) are caused by air contact, and can be reduced by using airtight containers rather than clingwrap or keeping the meat in the store’s packaging.ref Freezer burn is only a quality issue, and can be cut off before or after cooking, or ignored.ref

Nutrient content may decline a little for some frozen foods, but much less quickly than from other storage methods.ref It’s best to freeze food as soon as possible, when the original/starting quality is higher. ref

In contrast to fridges, freezers work better when kept full. A full freezer should keep its contents frozen for two days without power, twice that of a half-full freezer.ref As a rough guide, a freezer at the correct temperature keeps ice cream firm but not so hard that spoons bend.

Defrosting & Reheating

Microbes reactivate once unfrozen, building up their population and adding toxins to any that were present from before freezing.ref

Similarly, freezing pauses but doesn’t reset progress towards a use-by date. For example, you buy meat that is five days away from its use-by date. You put it in the fridge for three days, then decide to freeze it. When you defrost it a month later, it technically has two days left in which it should be used.

The challenge with benchtop defrosting is that the food’s surface may spend hours in the temperature danger zone before the centre has thawed. It’s safest to defrost in the fridge, though because it’s so slow it does require planning. The next best option is to quickly defrost by applying heat, which for most of us, means using the microwave.

So to defrost, a microwave relies on heated sections of the food slightly thawing the neighbouring frozen sections. Those sections can then be heated a little better, and in turn will defrost a little quicker and spread the thawing. This is why microwave defrosting is slow: the defrost mode is a long alternating series of heating and pauses while the heat radiates. It’s also why stirring is necessary, and why microwave instructions often stipulate a standing time after cooking. Both of which I typically ignore, to my own detriment.

Put one cup of tap water in a glass measure. Place the water in the microwave oven along with (but not touching) the utensil to be tested. Microwave on high 1 minute. If the utensil feels warm or hot, it is not microwave safe because it contains metal in the material or glaze. Do not use it. The utensil and/or the bottom of the oven might crack if microwaved.ref

The same rules apply to reheating as to the initial cooking, such as heating thoroughly, and using appropriate containers (e.g. chemicals can migrate into food from non-microwave safe plastics).ref

Refreezing, Re-reheating, Re-refreezing, And So On

The conventional wisdom is that food shouldn’t be refrozen once thawed. But like much conventional wisdom it’s not quite right. There is no specific safety reason against refreezing defrosted food.ref ref

Again, the things that matter are minimising the time in the temperature danger zone, and avoiding cross-contamination from unclean food and objects. While quality will deteriorate somewhat, it’s safe to repeat this cycle many times, provided the food is defrosted, cooked, and frozen/refrigerated properly.ref

Mouldy Food – What Can Be Rescued?

Moulds (or mold in US English) can cause respiratory issues, and some produce harmful toxins. They can grow at fridge temperature, spread by releasing spores, and are more tolerant than bacteria to sugar and salt.ref

Mould toxins can be held inside the mould or can spread through the food. Remove the toxins and the mould itself and the food safe to eat, but that’s easier said than done. Mould spreads more easily in food that is moist, soft, or porous, and it is difficult to locate completely. Soft or processed cheese (e.g. brie, any shredded cheese), soft fruit and veg (cucumbers, peaches, tomatoes etc.), sauces, bread, most leftovers, yoghurt, cakes – foods like these should be binned once mould appears.ref

Salvage is possible for hard foods, like carrot, capsicum, hard cheese, and salami. Excise all visible mould plus a 2cm margin.ref

Eggs

If you’re about to use some eggs but aren’t sure whether they’re still good to eat, try the float test. An egg that floats in a bowl of water has gone bad – it floats because of the rotten egg gas now inside. Eggs that sink are fine, while those that stand on one end are past their prime but probably still edible. Note this doesn’t test safety, only quality.ref So while it can save you from adding unpalatable eggs to your cake mix, to prevent illness you must rely on proper storage, the use-by date (if present), and adequate cooking.

Recap / Key Points

If you’re feeling a little overwhelmed, that’s understandable. Even the experts are still learning.

I find that rather than remembering every tip, it’s better to understand and then apply the basic principles:

- We can’t sense harmful microbes, so instead we must manage the temperature of any dangerous foods (e.g. meat, dairy, processed fruit & veg).

- Dangerous foods should be safe for at least 4 hours between 5℃ (40℉) & 60℃ (140℉) i.e. out of the fridge, particularly if kept near the extremes of this range. ref ref Refrigeration gets you roughly a week. Freezing lasts indefinitely. All times are cumulative.

- Cooking to 75℃ (165℉) kills pathogens but not their toxins. After cooking, spores can reactivate or new contamination happen but so long as the food is chilled fairly quickly then the above clocks largely reset.

- The above applies equally to defrosting/reheating/re-freezing. As long as you manage the temperatures and preferably reheat it thoroughly then you can defrost and re-freeze as often as you like.

- Apply the rules more rigorously with dangerous food that won’t be cooked, for instance salads, or sandwiches with egg or processed vegetables. Even diligent handling on your end may not be enough, as the food can already be contaminated with sufficient pathogens to make you ill. And because there’s no proper heating, any viruses from other people or pathogens that have been growing there are going straight to your belly.

Remember those points and you’re pretty much set safety-wise. For everything else, feel free to do what I’ll be doing and use this article as a reference next time you’re wondering which way it was that you were meant to be doing something in the kitchen.

Post-script: So…Can I Eat This Leftover Take-Away Food?

This was the question I first set out to answer, and yet it’s actually been the hardest nut to crack. To be honest, I’m not confident I have the answer, but this is a real-life (if First World) problem and sometimes we need to make decisions based on particularly imperfect information.

So this is what I’d do. Assuming it contains at least some dangerous foods (meat, dairy, processed fruit & veg etc) then I’d be confident eating it after one week.

I’d reduce that time, say by a day or two, if it wasn’t going to be reheated properly or if it sat out for a long time before refrigeration. Or if I had a compromised immune system. If it was mouldy I’d bin it, and if it shows other signs of deterioration it is probably still safe, but I’d be more cautious.

Going the other way, if it was leftovers from something I cooked then I’d be more lenient, since I’d have more confidence that it was prepared sanitarily, and it would likely have spent less time in the temperature danger zone.

But hey, it’s probably best if you just get your servant to whip you up something fresh. For the rest of us, it’s still a roll of the dice. But having spent many many hours looking into this topic, I’m now weighting those dice more towards eating that half-container of leftover Massaman curry.

Did you like this article?

Do you like this site?

Yay!! Has been too long between articles!